Conducting a Mock Lesson

- Yay Math!

- Jan 21, 2020

- 4 min read

Updated: Jun 24, 2020

This blog series documents how our network of schools became interested in lesson study. We have shared how our lesson study teams got started – by creating a shared vision of their hopes and dreams for students, determining a research question and theory of action, narrowing in on a specific content area for their research lesson, and then exploring the mathematical content and selecting a mathematical understanding goal and an equity goal for their research lessons. We have also documented our first three public lesson study events, a 3rd grade lesson on comparing fractions, an 8th grade lesson on negative exponents, and a 10th grade lesson on quadratics.

After the weeks of learning about their focus students, looking at student work, researching mathematical concepts, and anticipating student thinking, our research teams were ready to test out their research lessons. Even though the idea of lesson study is not to have crafted the perfect lesson (if there even is such a thing), teams found it helpful to do a dry run through of the lesson beforehand. Teachers who would be conducting the teams’ lessons reported that having the opportunity to practice the lesson launch and questioning strategies while their team could provide live feedback made them feel more prepared for rolling out the lesson with their students. For teams that had invited colleagues and community members, this step felt even more valuable. It is a vulnerable and brave space to be – sharing your teams planning and teaching your team’s lesson publicly in order to learn and grow – and the extra preparation was comforting.

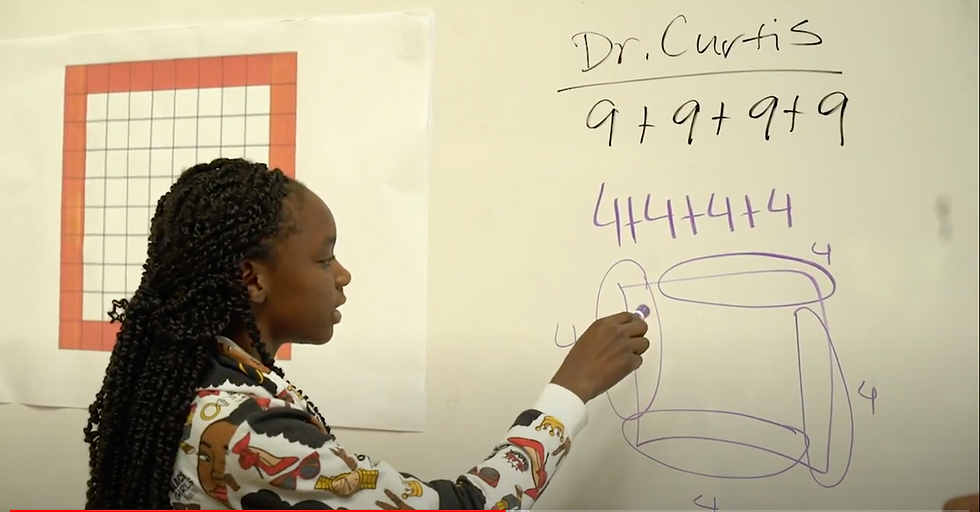

To conduct the mock lesson, each team member reviewed their anticipated focus student thinking, and then assumed the role of that student in the practice lesson. The teacher teaching the lesson runs through the lesson launch while team members share the anticipated thinking of the focus student they will be observing. They also share what else they think they may hear from students.

Are there other student ideas that may surface that the teacher could build from or make connections to?

What questions would be good to ask if these ideas surface?

Which questions would push the group towards the mathematical understanding goal?

What if no one says what you hope they say? What could you ask?

This supports the whole team in realizing what might happen during the lesson and plan accordingly. Not to scare teams off from doing the practice lesson, but sometimes detailed questioning strategies or entire lesson plans undergo significant changes during this time! This is perfectly normal! Our 10th grade team switched up the task from a diving board question to a ball toss competition question the weekend before their research lesson, because they realized that some of their students might not have experience with diving boards. They realized that while Sarah, the teacher whose class would do the research lesson, couldn’t ensure that every student had jumped off a diving board, she could take her students outside to experience throwing a ball in the air.

Since this last minute revision story spread throughout the network, teams have started using a culturally responsive rubric during their lesson planning to boost student access to the math (see agenda #6). While we’re still early in the process of exploring how to make our lessons more culturally relevant for our students, we’ve seen positive shifts in engagement when lessons align with their experiences and interests. A ninth grade team used class data about travel times to school to analyze lines of best fit and had 100% of students participate in the discussion, and an 8th grade class analyzed housing prices from nearby neighborhoods to explore unit rates and wound up having a whole class discussion about the possible reasons for the differences in price per square foot they were finding for different neighborhoods.

Teams also found it useful to have the equity or content commentators involved in the mock lesson, or even earlier in the planning process. The extra discussion and review from an outside perspective was useful for the team’s planning, and the increased understanding of the team’s context and focus students helped content and equity commentators deliver more targeted insights during their post-lesson comments.

For educators looking to try lesson study in their own contexts, we found it helpful to:

Run through the whole lesson. We acknowledge that some people love role-playing while others find it terribly awkward. However, we’ve found that running through the lesson and sharing student thinking as the team thinks the students would actually say and do the task , is incredibly helpful for testing question strategies.

Recognize that the goal of the final research lesson is not to create the perfect lesson, but to test a new idea or evolve an existing practice – it is meant to be an experiment, not a performance.

Practice the pre-brief. What is important for the team to share with colleagues or the community before they observe the research lesson? Examples can be found here (scroll to bottom of page), here, and here.

Daisy Sharrock works at the Center for Research on Equity and Innovation at the High Tech High Graduate School of Education, and is part of a Student-Centered Learning Research Collaborative-sponsored research team that is currently engaged in the following study: Leveraging the Power of Improvement Networks to Spread Lesson Study. Read more about their current study here. We are grateful to JFF, KnowledgeWorks’, and the Student-Centered Learning Research Collaborative and its funders for their support. Learn more at sclresearchcollab.org

Comments